Iron Aria

by Merc Fenn Wolfmoor

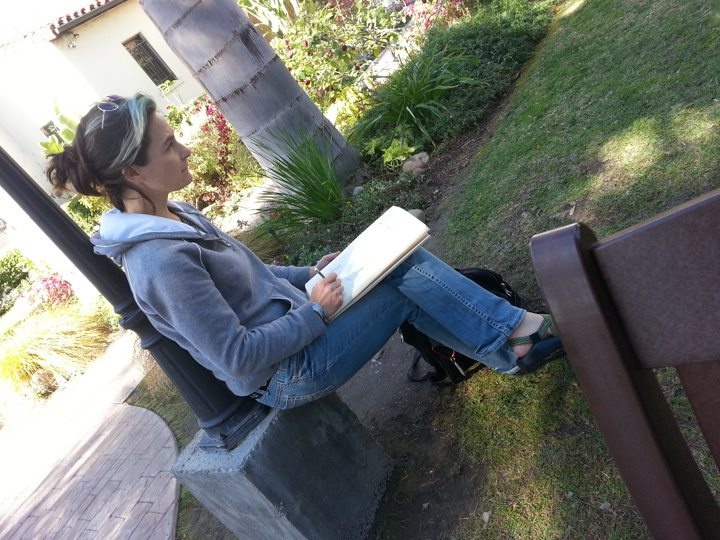

Illustrated by Galen Dara | Edited by Brian J. White

| Selected by Daniel José OlderJuly 2016

The mountain dreams pain. Cold iron vibrates purple-blue deep in the stone while tongues made from rot and rust bite and gnaw and hunger ever deeper. The dam, buried like a tooth in the mountain’s narrow gums, holds back the great burgundy ocean. Otherwise it would pour into the Agate Pass valley and swallow up the mining town at the mountain’s toes.

From an owl’s eye, the dam is almost as big as the mountain, built five hundred human-years ago. The infesting tongues burrow in from the sea, sent by angry water-memories. The sea cannot see its children in the lakes far beyond the dam. So it sends corrosion into the mountain, into the infinitesimal pores of the dam.

The mountain is being devoured from the inside and it screams.

Kyru squints up at the mountain in the moonlight.

It slopes massive and muscled against the ice-black sky. The mountain’s dream-noise woke him from his own nightmares — the loudness of steel blood breath, of his mother’s last words — and he shivers in the late autumn night. Snow will come soon, blown in salt-scented gusts from across the ocean on the other side of the dam.

He sits on his windowsill, the shutters thrown open. It is only one floor’s drop to the burlap-covered garden below and then twenty steps to the forge, where his heavy boots and thick gloves hang on pegs, where his rucksack, stained from coal dust, waits with his leather apron.

He has never trod up the mountain, so he doesn’t know how many steps it would take.

The miners’ cart trails are well-worn and wide, easy to walk. He could be gone before dawn and not missed until—

That is where his plan falls to pieces like shattered crockery. His aunt would know he had disappeared within the hour. He apprentices to her in her smithy; and the only routes away from town are up the mountain or down the valley.

He hates the valley. Its floor is littered with unknown graves, mournful bones, his last memories of his mother and sister. He craves escape and does not know how to unearth it. Dawn chips away the clouds and it is once again too late again to run.

“Kyra?” his aunt calls from the kitchen. “Get dressed. It’s a long forge day.”

He flinches at the wrong-name, slipped like a needle under his skin. He climbs from the chill window and grabs the heavy leather belts he uses to flatten down his chest before he pulls on his shirt and trousers.

In the kitchen, his aunt straps on her leather apron as her husband scoops warmed day-old oatmeal into trenchers for the three of them.

Kyru shuffles to the table, his sketchbook under his arm. Mint and honey spice the breakfast. He gulps his warmed cider to keep from having to speak.

His aunt shovels her oatmeal in huge bites, saying around mouthfuls, “We got a big order from Brynu down at the farrier’s. He’s armoring some new plough horses for hauling ore through the Crags. He doesn’t want to take chances on the wolves being hungry this winter.”

Kyru nods.

“Kyra,” his uncle says with a sigh, “what are you wearing in your pants? Another bunch of sackcloth?”

Kyru scoots his chair closer to the table so his uncle can’t see his lap.

His aunt shakes her head and shoves her empty trencher aside. “She’ll get over it eventually, Dyru. Be glad she’s as skilled in metallurgy as her mother, ages rest her memory.”

His uncle shrugs and clears the table. “Well, at fifteen I’d hoped she’d be eyeing herself a suitable husband by now. Folk talk more and more, you know.”

“Eh, let folk talk. Long as Kyra pulls her weight in the forge, she can put off the men for years for all I care.”

He has no interest in marriage, to another man or not. He’s never been attracted to other people the way everyone else places such value in.

When he dreams of escape, he pictures himself in his own forge, content with metal-song and the warmth of burning coal, visited only by people who call him by his true name.

His aunt claps her hands, brisk and loud. “C’mon, the farrier’s armor won’t forge itself.”

Kyru’s stomach cramps. He leaves his meal unfinished.

The bitter air warbles at his ears. Pleasant gray chill washes the kitchen heat off his skin.

He looks up at the mountain. Over the dam lies the sea. He has never heard of water caring the make of a person’s bones and flesh. It all sinks in the end.

“Kyra,” his aunt snaps from the smithy door. “Daydream at lunch.”

Kyru ducks his head and shoves his hands in his pockets. Even the promise of singing to the metal — when his aunt can’t hear — is dulled by her impatience.

He hears the soldiers’ swords before the town’s alert bells sing.

A regiment of one hundred soldiers in emerald uniforms and sun-bright armor marches into Agate Pass, the Lord High’s brilliant banners snapping in the cold air.

The town of Agate Pass is the last frontier-hold on the mountain. Other towns in the region have withered and crumbled, but Agate Pass holds fast. The dam was supposed to bridge commerce, power great wheels and generate trade and wealth through the valley.

But dour luck has clung here for generations, the dam now only a bridge through the mountain passes to the flatter lands in the empire outside the valley.

Kyru watches, his legs rigid, from behind the cedar fence that corrals the geese into the yard beside the forge. A half-dozen imperial knights, their plumed helmets shaped like roaring lions, stride towards the smithy.

Miners readying for work edge along the road, watching.

“Smith,” the knight at the front calls, deep voice rich and thick like the hair that coils down over his breastplate in a thick braid spun with ribbons. The gold leafing along his shoulder pauldrons marks him as a general.

Kyru’s aunt shuffles past him, out onto the front stoop of the smithy, and bows low. “Welcome, Hands of the Lord High.”

As the knights draw nearer, their armor hums with wariness. Agate Pass has not received a military envoy in two years, since the Summer Census. It’s not the town that unsettles the armor’s folds and joints, but the dam.

All the knights’ armor can feel the wrongness welling from the sea.

A trumpeter, his throat replaced with a gilded cage and thrumming gears, announces that the Emerald Lion General and the Imperial Hands are closing Agate Pass’s mines. By the Lord High’s order, the mines will be closed until reports of instability in the dam can be confirmed.

As the general strides closer, Kyru notices the general’s armor. It is suffering. It keens low, stoic. A burning pain lingers from the battlesmithy done on the road, incomplete, which left unseen scars.

Kyru can always hear the voices of metal, like strings sewn through his skin into his heart. He stuffs the cotton strips he uses in the forge in his ears to dull the outside noise.

Can I help?

The armor shivers. Echoes, stolen breath, wailing dead—

Kyru flinches and presses his body against the fence, watching through the slats. The armor imprints its experience on his senses: hard angles, scalpel edges, glittering passion, and vicious duty.

Where is your pain?

The armor shows a memory of the dent when an ax caught in the breastplate’s folded steel over the sternum. Now metal seams pinch there like crooked nerves.

Dust of kin scattered knife-sharp – buried – blood – stricken –

Kyru rubs his arms above the copper bracers he wears. They belonged to his mother, forged by her hand when he was born. She wrought them with sigils to give light in darkness.

By that light he found his way to Agate Pass the night his mother died.

The general pulls off the helmet and tucks it under one arm.

The general’s features are heavyset, highlighted with rouge and eyeliner, lips colored coral-pink. A coiled sigil, whorled threads branching leaf-like from delicate roots, is tattooed on the soldier’s temple, just under the edge of hair.

Kyru recognizes the symbol, often painted on skin in the bigger cities: it denotes feminine gender, subtle and elegant.

The general is a woman.

Kyru’s heart trips. She is like him, only opposite. He’s seen other men with the masculine symbol: waving lines like a river, encircled in a sharp-edged sun. He scratched it on his cheek in charcoal once, but washed it clear before his aunt saw.

“Smith,” the general says again, “a word.” She strides up the path and into the shop, and Kyru follows as if magnetized.

Two knights wait outside the door, none following the general into the smithy. Kyru slips in like a breath of smoke, scarce noticed.

The general’s words hum deeper and richer than his aunt’s as the general lays out curt orders. Kyru ignores the two women’s voices and sidles towards the general’s back.

Can I help? he asks, tentative. I will be gentle.

The armor murmurs umber-toned consent. He touches his palm to the breastplate’s back; he feels no defensive runes, no static snap of angry magic. He shuts his eyes and spreads his focus out along the damascene plates. With gentle nudges, he unfolds the pinched seam and unweaves the battlesmithy, then smooths over the wound. The armor’s pain ebbs and the breastplate brightens in gratitude—

A hand seizes his wrist and yanks him around. Kyru sucks in his breath, his body taut. He is face to face with the Emerald Lion General.

“Who are you?” the general demands. “And what are you doing?”

“It was hurting,” Kyru says, scarcely audible.

“Please forgive her, general,” his aunt says, twisting her fingers around her forge belt. “She’s highly skilled in metallurgy but—“

“‘She’?” The general’s eyebrows arch. She releases Kyru, who stumbles back, breathing fast. To Kyru, she says, “What’s your name?”

“Kyru,” he whispers. It is the only word that never hurts.

It was the last word he told his mother ten years prior. She asked him, What shall I call you, child, when I see you from the heavens? He told her his name. Then the curse turned her bones into brittle slivers and her skeleton collapsed in on itself.

“And are you a woman?” the general asks.

Kyru shakes his head, his heartbeat like hot gold booming in his ears.

“A man, then?”

Kyru nods, his breath scattered wisps in his lungs.

“I thought as much.”

To his aunt, the general adds, “I advise you show your son more respect.” She flexes her gauntlet and turns for the door. “My lieutenant will pay you for the forge’s use and expenses. My smiths will remain here until called for.”

She sweeps out; her knights come to attention as she passes. Kyru dashes after her before his aunt can stop him. He catches the door on his shoulder.

He dismisses the bruise. It’s a dull sensation, a deep ache he prefers to sharp cuts.

“Wait.” Kyru swallows. His tongue itches. The words clink and scrape, wrong angles and too loud against his teeth. “I can help.”

The general holds up her first, the steel gauntlet attentive but wary. Her retinue halts. She turns on one heel, a great owl-movement, fluid and terrifying. “How?”

Kyru points up at the mountain. He pushes sounds against his lips despite the pain. “I hear what’s wrong.”

The general studies him, her dark eyes like mica. “Hearing and helping are not the same.”

He lifts his hands. “Your armor. I healed it. Can…do that…with the dam.”

It is a chipped truth, not whole. His ribs tighten in fear she will see it and grow angry. He has never touched the dam; he knows its construction only from the architectural drawings housed in the town census hall. As a boy, he sneaked away to lose himself in the drawings of the great dam. He imagined it folding around him and shielding him from the loud, cold world.

After his mother died, after his aunt filed legal claim to raise him, that was all that kept his tears from drowning him.

For the last two months the mountain’s dreams have drifted through his thoughts, inescapable. If the dam is not healed, if the mountain is not soothed, everything in the valley will be washed away.

He does not remember where his mother’s and sister’s bones are, but they should not be churned up and scattered. He does not want to see Agate Pass again, but he does not want it to die. At last, the general nods once. “Come with me, boy.”

His aunt and uncle protest, but the general hears none of it. In a few terse words, she conscripts Kyru into the Emerald Lion Regiment and tells him that from now on he is in service to the Lord High and Her Holy Empire.

There is no room for sickly, mold-green fear in his chest when he falls in step with the general’s silent-footed guard. They head up towards the mountain. The mountain’s pain is too vivid, too cold and heavy as it pulls at his thoughts.

Yet even the great vastness of stone cannot erase his worry: will the general send him back when his use is finished?

The day-long trip up the mountain has brought the regiment to the foot of the Tilted Stairs, a great staircase carved into the stone that leads to the mines and the cave systems inside. From this campsite, Kyru sees the dam in full for the first time.

The Agate Pass Dam expands between the mountain’s cleft, as long as hundred wagons, as thick a dozen horses standing nose to tail. Age seeps through the old stone, heavy burgundy teased with gray. He gets only a glimpse before the nauseating swell of mountain-pain washes through him. He sits down on one of the steps, dizzy.

The knights’ retinue set up camp, and Kyru wonders why the Lord High would send so many soldiers. He dares to gesture, faint and quick, at the armored men and women around him as he looks at the general in question.

She offers a half-smile. “The last two expeditions sent here haven’t reported back,” the general says. “I’ve had reports of maddened animals and crazed bandits. What have you heard?”

He ducks his head. “Hurt.” The general grunts. “Look, boy. I know desperate when I see it. But you’re still an unknown element in my plans, do you understand? Your metallurgy will prove useful, but I want you to stay out of my engineers’ way when they arrive. Let us do what we’ve come here to do.”

He nods, shrinking inside as he hears: you cannot help. Is that his curse? He couldn’t save his mother and sister. He can’t change his body. He can’t heal the mountain and the dam.

Night lowers its curtains, starless and full of clouds. Kyru keeps the cotton in his ears against the clamor of cheerful pots and sarcastic ladles. The knights’ armor is restless, anxious this close to the mountain. Only the Emerald Lion General’s mended armor seems calm.

Kyru pulls out his sketchbook and flicks charcoal over the thick paper. The smoothed pulp soothes his fingers while the copper bracelets murmur comfort into his bones from wrists up to his jaw. He hunches over nonetheless, using the slope of his shoulders to hide the awkward bulge of his chest in profile.

He draws what he hears in dreams, what the mountain’s nightmares show:

The furious ocean, hurt and mourning children dying far from the parent waters, stripped of salt and memory. The metal cannot see which way to go. Veins of ore twist and writhe while the great iron beams sunk long ago into the consenting stone—

“…we lock down the tunnels in the morning,” says the Emerald Lion General. Her name is Tashavis. She sits cross-legged with her boots polished and standing to attention at her side as she paints her toenails a luminous green. “The engineers can examine the dam and find the source of the disturbances. Has Zasa reported back yet?”

“Not yet,” one of the soldiers says, her jawline grim. “I’ve had no word from her since she went up this morning.”

Kyru chews the inside of his cheek. Dawn is so far off. He walked in silence beside the general most of the day, but each step deepened the unease in his belly. The mountain’s pain is growing worse. He is not sure they have until dawn.

He flips through his sketchbook, his fingers tracing familiar pictures as he looks for an unused page. He must illustrate the urgency to the general. There is little space left on the paper.

Tashavis jerks her head at her soldiers. “Set a double watch. Everyone, light rest — we move at dawn.”

Kyru sits just close enough to the fire to see his paper and feel the fringe of heat, but not too close to the soldiers. As the knights disperse, he edges closer to the general. Her armor hums welcome and he offers it a tiny smile in return.

“General?”

Tashavis glances at him. “Ah, Kyru. How’s your first day of conscription?” She flashes him a smile. “Not quite the excitement you pictured, I imagine.”

He hesitates. Despite his aunt’s refusal to call him by his true name, they’d developed a useful shorthand in hand gestures when in the forge. He does not have such luxury with Tashavis.

Kyru bites his lip. “No.”

“You’re an artist,” Tashavis says with a nod at the sketchbook. “My brother likes to paint as well. You’ve heard of the Dragonfly General?”

Kyru shakes his head. He doesn’t want to interrupt her — but he needs to make her see. They can’t wait until dawn.

Tashavis chuckles. “Well, he didn’t earn the title through paints, admittedly. I’ll tell you war stories later. What’s this one?” she asks, her eye cornering the open page. It’s Kyru’s self-portrait, the one he made when he first saved his pay from the forge to buy the paper and charcoal. He placed it in the middle of the sketchbook, a single blank page beside it.

Kyru rendered his dream of changing his skin onto the paper: becoming smooth, polished metal—androgynous planes to flatten his chest and hips, his bones wrapped in copper and his skull hairless, domed in bronze. He would have steel mesh fingers, flexible and strong. His ears would be replaced with tiny mechanical doors he could close to keep out noise when he needed silence. Deep iron for his throat and lungs, to lower the timbre and register of his voice. A metal boy, but impervious to heat and sound: a perfect smith. He would train his skin not to feel unpleasant textures so he could dress how he liked. His eyes would be silver, with gold pupils so he could stare into the sun without becoming blind, and see far, far into the night sky to watch the stars dance amid the coal-deep spaces between.

He dares not shut the book and hide it now that she’s focused her attention on him. Hesitantly, he points at himself.

Tashavis extends a hand, and Kyru sets the sketchbook on her palm. His fingers shake. She pulls the sketch closer, her gaze sweeping like an unstoppable tidal wave over his true self rendered in charcoal.

“It’s beautiful,” she says, and hands him the sketchbook back. “You capture your likeness effortlessly.”

Kyru blinks, his mouth sticky-dry with surprise. He accepts his sketchbook.

“I’m glad you know yourself, Kyru. I was twice your age before I found the courage to show who I was, even to myself.” She adorns her nails with quick, sure strokes. “All persons deserve to have their names and bodies respected.”

Pain prickles at the base of Kyru’s spine, twinging the skin of his hips. He stiffens and lifts his chin. It’s not noise, but he feels old metal, burned and soured with salt, hateful and hurting. He jabs his finger at the far edge of camp where the metal draws nearer. “Someone’s coming.” The words dig at his gums, splinters under his tongue. He spits them out fast. “Dozens. Angry. Want to kill us.”

The general snaps to her feet. Her paints tumble in green-blue pooled stains by the fire.

“Swords ready!”

The camp unfolds like a fierce steel trap, soldiers springing to attention. A gurgle comes from the edge of camp.

A severed hand skitters through the dirt clutching the warning whistle.

The general curses and draws her saber. Kyru claps his hands over his ears.

From the shadows outside the camp, skeletal figures in moldy leathers covered in crustaceans stagger forward, carrying the smell of brine and flotsam in a heavy miasma. Seaweed falls from eye sockets long rotted out. Mouths hang agape, teeth broken like mollusk shells, salt dripping from exposed bones and calcified flesh. The bandits’ hands have been replaced with the remains of old swords, hooks, saws. The metal seethes, dragged from the deeps to the stinging air, denied oblivion. Rusted threads corroded by the ocean hold the dead bandits together.

The soldiers crash against the undead bandits. Pulled from the sea, those bodies are fueled with rage and hunger — like the ocean, like the mountain’s pain.

Tashavis strides towards the invaders. Her armor brightens with war sigils — fiery green with deeper highlights until her breastplate glows with a rampant lion and the armor roars. “Kyru, go! Get to safety!”

Kyru runs the only direction open to him: up the mountain.

He bruises his toes and shins as he scrambles up the steps. The copper armbands glow faint amber to light his path, but it hardly pushes back the dark.

Into the mountain, where the air is damp and cool, he hears the old metal in the stone’s veins. Mining tunnels. He read a memoir from one of the first miners in Agate Pass, one of the stone masons who scooped out trenches into the rocks between land and sea with her bare hands—

Kyru keeps the illustrations from that book in his head, traces the woodprint edges with careful memory. His favorite was the one of Mason Irusa, standing on the mountain, holding a great boulder aloft as if about to throw it into the sea. There were maps in the book, too, like worms wriggling through the paper, inky trails to show where the original mines had once been excavated before it was deemed too dangerous and the passages were closed, and new tunnels developed further down the Stairs.

Deeper, he runs.

The metal cries out louder, thundering in his thoughts. His ears begin to bleed, hot itches that crawl down his neck.

PRESSING. DROWNING. WRITHING. BURNING.

Kyru stumbles and lands hard on his knees. Here the tunnel branches, but he can’t remember the map. In his memory, the pages keep blurring. Which way?

Instead, he sees his family: himself, his mother, and his sister, with their few belongings, pushing through the forests from the coast up towards the mountain. They fled the ruins of salt-washed boards and icy ropes, all that was left of the shantytown — their home — after the unhappy waves destroyed it.

In the forest, along with the few other persons and broken families who had survived, they came to a wide stream, dark and rippling with unanswered voices.

From those waters rose the old dead, left to rot for so long.

He wasn’t near enough when the old dead attacked. He’d been looking for the perfect stick to make a sword, so he could become a guardsman for the Lord High. He heard the screams — his sister’s, first — and then his mother’s clarion voice invoking a death-curse that would shatter all the dead. His mother saved half the people in their little band of survivors.

He ran back, wielding his stick, terrified, but when he found her, the damage was done. The old dead were no more, and his mother lay dying beside his sister’s tiny body.

If he had been there, perhaps the old dead would have gone for him first, not little Zyra.

RAGE SLUICING. THICK, COLD, UNBEARABLE. IT HURTS, IT HURTS, IT HURTS.

Kyru presses his palms against his ears. The metal jars him from memory, from guilt. Too loud too loud too loud.

Stop!

IT BURNS, the metal cries. IT CONSUMES. IT TAKES ALL.

Kyru fumbles for his sketchbook, rocking on his heels, then realizes he left it in camp. He has nothing to ground himself with. He squeezes his eyes shut, clinging to his copper armbands. Need to think. Need the red noise to go away.

Can’t help you when you shout. It comes out a cracked whisper, a thought sent to the metal and stone. Please. Please. Stop.

Slowly, too slow, the metal voices dim and settle, pulling the pain inside so it doesn’t spark and wash over Kyru in blue-hot waves. Kyru breathes deep, pictures pink copper roses and bronze lilies shaped with touch and heartbeat.

CAN YOU HELP?

Kyru keeps the flowers in front of his eyes, keeps breathing. His neck is stiff, orange-sore, but he can dip his chin. Nod.

Yes. Careful, quiet. Unlike before — with his family, with himself. The metal and the mountain can yet be saved.

Yes, but you need to listen softly. We can’t let the rot hear.

Kyru presses his hands against the mountain’s skin.

He can feel the dam, a mastery of old smithwork: great steel beams, fibrous mesh, and iron braids wound through uncounted tons of stone in a dam that holds back the sea. It’s hurting, chewed away by the rot. The dam’s umber pain echoes back against Kyru and he bites the inside of his cheek to stop it spilling out into the mountain even more.

Let me help you, he says, desperate. Please.

The mountain gives consent.

Kyru shows the new iron where to slip through cracks in the mountain’s bones, guides the tendrils towards the dam. The metal follows his will, echoing back into him until there is only a call and response like heartbeats: his to the mountain’s, the mountain’s to his.

HURRY, rumbles the supports in the wall. THE WATER PRESSES.

Kyru’s arms tremble. Sweat itches his face, stings his eyes. The blue pain echoes through his gut and up to his jaw until his head feels too heavy to stay attached to his neck.

Pressure like a hundred tons of ore raw to the forge bangs against his bones and his footing slips. No. He must stay — must stand — must—

The dam groans again.

Kyru feels his muscles fray, ligaments cracking, skin seeping iron shavings as he guides the metal ever onwards. It will rip him to pieces, melt him like copper.

The mountain shudders and Kyru wants to scream.

He. Will. Not. Let. GO.

Iron fills the cracks, wraps itself around its siblings worn with rust, binds to stone, nets the dam from the inside until a new web of cold iron stretches between the mountain’s gums like a tooth cap and the dam is healed.

Kyru falls into white silence.

The mountain no longer dreams pain.

It has let the ocean send soft memories through the absence of iron, drifting in stone to flow out in a new waterfall far from the town. The stream will wind through forest land and over dried rock and touch the lost lake-children, the saltless now remembered and able to share dreams with the ocean after so long silent.

Kyru opens his eyes. He lies on bright sheets, his hands wrapped in gauze, his head brittle-full like a turnip sack filled with glass chimes.

“Don’t sit up,” says a deep voice, and he remembers it — the Emerald Lion’s. “You’re a lucky boy. The cave-in we dug you out from almost crushed your skull. The physician says your hands will heal, but it’ll take time.”

The room drifts into focus as his eyes adjust to the light. Sunlight. He cannot smell the sea, only vinegar and lavender. He hears the contented hum of the general’s saber and the twining chirrup of scalpels and bone splints.

“Where?” he manages, lips swollen, the word scraping.

“Shale-Ar,” Tashavis says. “About a week’s ride from your old town. Whatever you did affected the curse from the dead. They dropped like wet clay, and then we heard the rumbles from the mountain.”

The physician, a woman with eyes as dark as water-soaked agate, leans over him and spins a tiny rune between her fingers. “This will numb the pain and help you sleep.”

“I…don’t…have…to go back?” he manages.

“No.” Tashavis smiles down at him, then lays a hand on his shoulder. “We’ve got another two weeks’ journey until we reach the capital. Rest, Kyru. The dam is secured, and you are still under my protection.” She shows him his sketchbook, the edges crumpled and the cover dented, and lays it beside him on the bed.

Kyru’s ribs loosen, and he pulls in breath.

Through the stone foundations of the physician’s house, down into the soil and stretching back through forest roots, Kyru can still feel the mountain again like a whisper in his heart.

The mountain looks over the valley, a truce brokered with the ocean, its skin sharing new memory with the waters as they did once, long ago.

The ocean’s wrath has subsided with the tide, and the lakes, reawakened, sing in joy.

Are you all right? Kyru asks.

Yes, the mountain says. Are you?

Kyru smiles. Yes.